Closing the net on the habitat needs of tiny fish

It is 3 am on a moonless night in June. In the depths of Plymouth Sound, a small camera springs to life. Its four lenses fix their gaze among the towering seagrass blades, suspended motionless in the gap between tidal ebb and flow. Amid the tiny crustaceans whizzing in the spotlight, a small sand smelt glimmers majestically then, with a panicked fin-flick, is gone. The cause of the sudden departure slowly fades into view—the sculpted flank of a large seabass. Five minutes later, duty done, data stored, camera and lights power down, only to wake again, hour after hour, day after day, in the quest to reveal the roles played by inshore habitats in supporting fisheries.

What habitats do young fish need?

The camera is one of 12 developed for the FinVision project, a Fisheries Industry Science Partnership (FISP) funded by DEFRA. Deployed in different habitat types for days or weeks at a time, these cameras are helping us understand what habitats fish need—information critical for designing management actions and policy decisions that underpin viable fisheries and successful nature conservation. In Europe, more than two-thirds of fish landed in commercial fisheries are known to rely on inshore habitats at some point in their life. Yet, coastal areas are on the front line of human impacts such as pollution, habitat destruction, and climate change. Notably, habitats like seagrass meadows, saltmarshes, and kelp forests, considered to be important fish habitats, have experienced substantial declines along UK coasts. Only with knowledge of fish habitat requirements can we understand how the loss or restoration of habitats impacts on fisheries sustainability and nature conservation.

Figure 1. Recreational angling groups such as BASS, key FinVision Partners, are important champions of nursery habitat conservation: seen here surveying juvenile seabass in Cornwall. © Ben Ciotti.

Even the most casual marine biologist will probably have some idea where larger, adult fish live, and century-long records of fisheries catches and scientific surveys provide a tremendous body of data. But the sought-after big fish are reliant on a precarious process of development through egg, larval, and juvenile stages which often don’t make it into the survey net. It is small variations in the already minute survival rates of these tiny stages that regulates the size of many fish populations. The issue is that young fish need habitats to survive—habitats that are often different from those required by adults. In many cases, it is this juvenile stage that has the tightest reliance on the shallow areas most impacted by humans, yet we know relatively little about the habitat requirements of juvenile fish, particularly the earliest post-larval forms.

The FinVision project is innovating new ways to observe, study, and gather critical data on easily overlooked young fish. Bringing together scientists from the University of Plymouth, representatives of the recreational fishing sector (Bass Anglers Sportfishing Society, the National Mullet Club, the Angling Trust) and management organisations (Association of IFCAs, Southern IFCA, Institute for Fisheries Management), a major focus of the project is on developing and testing new camera technology that can film tiny juvenile fish in the wild.

A new tool to understand fish habitat needs

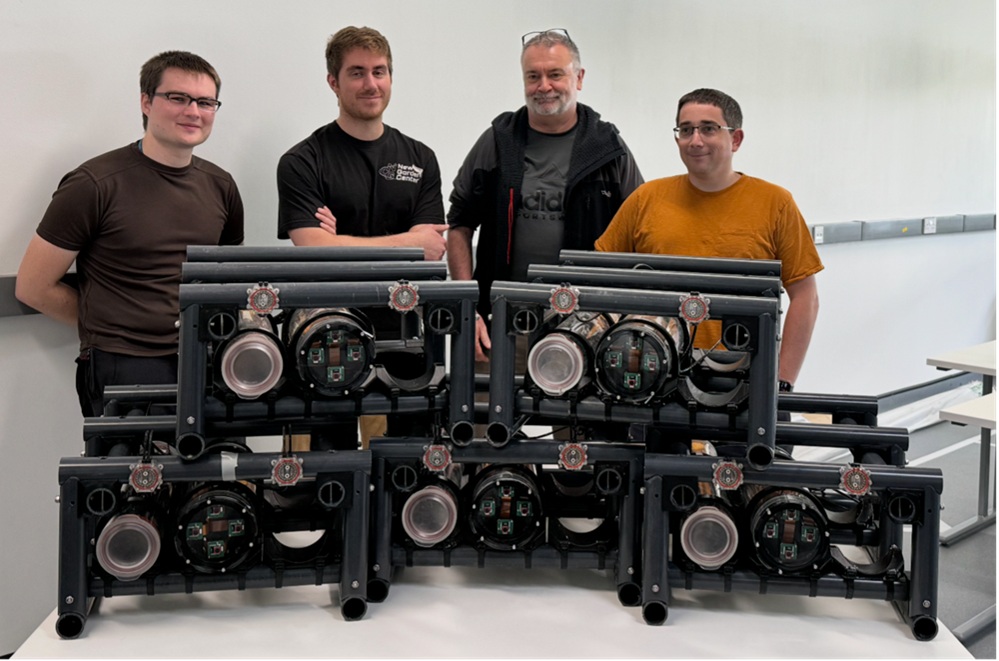

The JHaM-Cam (Juvenile Habitat Monitoring Camera) is a smart camera system specifically designed for monitoring juvenile fish (see Fig. 1). It has been designed and constructed by the University of Plymouth’s EmbryoPhenomics Team, in partnership with the Advanced Digital Manufacturing and Innovation Centre, both based at Plymouth Science Park. The camera has specific adaptations which make it perfect for the task. Most importantly, it has a bank of four cameras and integrated lights, enabling 24-hour visualization of the smallest, thumbnail-sized juveniles that often slip through other surveys. Run by an onboard computer, the JHaM-Cam has impressive power management capabilities and is able to operate independently on complex tasks of gathering video footage and environmental data for deployments extending over weeks. To set it running, scientists simply configure the deployment regime wirelessly from their mobile phone—before plunging it into their habitat of interest (Figs 2 & 3).

Figure 1. Innovative JHaM-Cam technology for the FinVision project has been developed by the EmbryoPhenomics team at the University of Plymouth. © Oliver Tills.

Those who have spent happy summer days with nothing more than a net and a bucket may ask why so much tech is needed. People have been catching fish from the sea for millennia, so are there not easier ways to see where fish are living? Certainly, more traditional approaches such as netting and diver surveys continue to provide essential information about juvenile fish habitat needs. But cameras like the JHaM-Cam are a necessary addition to the toolkit. They are particularly good at spotting the smallest fish that may not be seen by divers, or captured in net surveys, and can be deployed in a range of different habitat types. Furthermore, the continued day-night, week-long coverage is critical for capturing fine-scale changes in distribution. Work in the tropics suggests that habitat use of juvenile fish can be extremely dynamic, with important shifts and key processes occurring at the scale of a few hours. In coral reef fish that settle into juvenile habitats at night, for example, 60 per cent may be lost before morning arrives. Round the clock, long-term coverage increases the chances of capturing these important events. Nature is complex, and therefore innovation must be key to advancing the approaches we use to sample the natural world—particularly when we know that current methods have inherent limitations.

Figure 2. A JHaM-Cam system hard at work, observing how early juvenile fish use seagrass habitats. © Richard Gannon.

Figure 3. The University of Plymouth’s dive team return to the boat after deploying cameras in Plymouth Sound. © University of Plymouth.

So far, JHaM-Cams have been deployed across six habitat types in Plymouth Sound and the Tamar Estuary, and alongside a range of other netting surveys stretching from the Fal, Cornwall, to the Isle of Wight (Fig. 4). A total of 524 hours of footage, across 73 deployments, has revealed the daily lives of species such as pollack, mullet and sea bass. Data from the deployments is being used directly to advise management measures by the SIFCA and is forming the basis for new approaches to monitoring and research.

A window between worlds

As well as providing tools to gather much-needed data, the FinVision partnership is an important opportunity to widen participation in research and connect communities and institutions with the vital ecological role played by coastal habitats (Fig. 5). Hosting a number of online and in-person training events, the project also invites members of the public to view footage and record fish sightings through a public web portal hosted by Zooniverse. A quarter of a million clips have been analysed on the portal so far—further evidence of the staggering contributions that can be made by citizen scientists.

Figure 4. JHaM-Cam are being developed to complement netting survey efforts by Southern IFCA, to provide a more complete picture of how juvenile fish use inshore habitats. © Southern IFCA.

Figure 5. a) above. Volunteers using nets to survey juvenile fish as part of a FinVision training event run by the Institute of Fisheries Management.

b) below. A small goby is at the larger end of the fish being investigated in the project. © University of Plymouth.

Beyond data collection, the web portal represents an important window between two very separate, but interconnected, worlds. The web footage brings the dynamic world of marine creatures into the living room. From the violence of tidal flows to sublime scenes of colour and tranquility to the murky confusion of coastal habitats, this is the world young fish navigate at the very start of their lives.

Seeing beneath the waves inspires curiosity and educates about the role of marine ecosystems. It also brings a view of coastal habitats into the polling booth, the boardroom, the council chamber. It is 29 years since the USA, through the Sustainable Fisheries Act (1996), formally recognized ‘Essential Fish Habitats’ in fisheries legislation. Similar legislation does not yet exist in the UK or Europe, but momentum is building. The 2020 Fisheries Act clearly recognizes the role ecosystems play in sustaining fisheries, and the recent reorganization around Fisheries Management Plans provides a mechanism to insert habitat considerations into management actions. Projects like FinVision can advance our understanding of the habitat needs of fish, and will be important to achieve the robust, evidence-based approach required to create sustainable fisheries.

• Dr Ben Ciotti (benjamin.ciotti@plymouth.ac.uk).

Get involved:

Are you interested in learning more about the project, seeing some of the footage and maybe helping to collect data? Please visit the project webpage www.plymouth.ac.uk/research/marineconservation-research-group/fishing-and-aquaculture/finvision to learn more. Here, you can sign up to receive updates on the project and access the interactive web portal.