Reality check for marine protection

After years of work to identify and designate marine protected areas (MPAs) in the UK, we currently have 377 MPAs around our coasts, covering 38 per cent of our seas. These figures are often quoted and, indeed, the designation of many MPAs should be celebrated. But how are these MPAs really doing? Are they actually making a difference to the marine life they were designated to protect and recover? These are questions we have been asking for a long time at The Wildlife Trusts, but until now, picking apart this information at the national level has been difficult.

Marine Protected Areas in the UK are designated to protect specific habitats and/or species within their boundaries following a ‘feature-based approach’.1 Statutory Nature Conservation Bodies (SNCBs) report the condition of these individual features for each MPA but getting an overall picture of the state of the UK MPA network as a whole is difficult: information is spread across multiple web pages and documents and on different SNCB websites, depending on who is responsible for their monitoring. Realizing this, we decided to compile this information and undertake a UK-wide assessment—The Wildlife Trusts’ MPA Recovery Check Assessment was born!

Information was gleaned from SNCB reported condition assessments (where features are monitored and assessed against their conservation objectives) or vulnerability assessments (where the degree of exposure to pressures the features are known to be sensitive to is assessed, often used as a proxy when no specific monitoring information on the condition of features is available). When neither condition nor vulnerability assessments were available, the General Management Approach for the feature was used (the advised approach to bring the feature into favourable condition: ‘maintain’ if it is thought to be in favourable condition already, or ‘restore’ or ‘recover’ if it is thought to be in unfavourable condition).

Puffins in the Farne Islands, Northumberland, England. Among other designations, the Farne Islands are a Special Protection Area (SPA), and home to an internationally significant breeding colony of seabirds and Atlantic grey seals. © Hansheap, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The state of UK MPAs at a glance

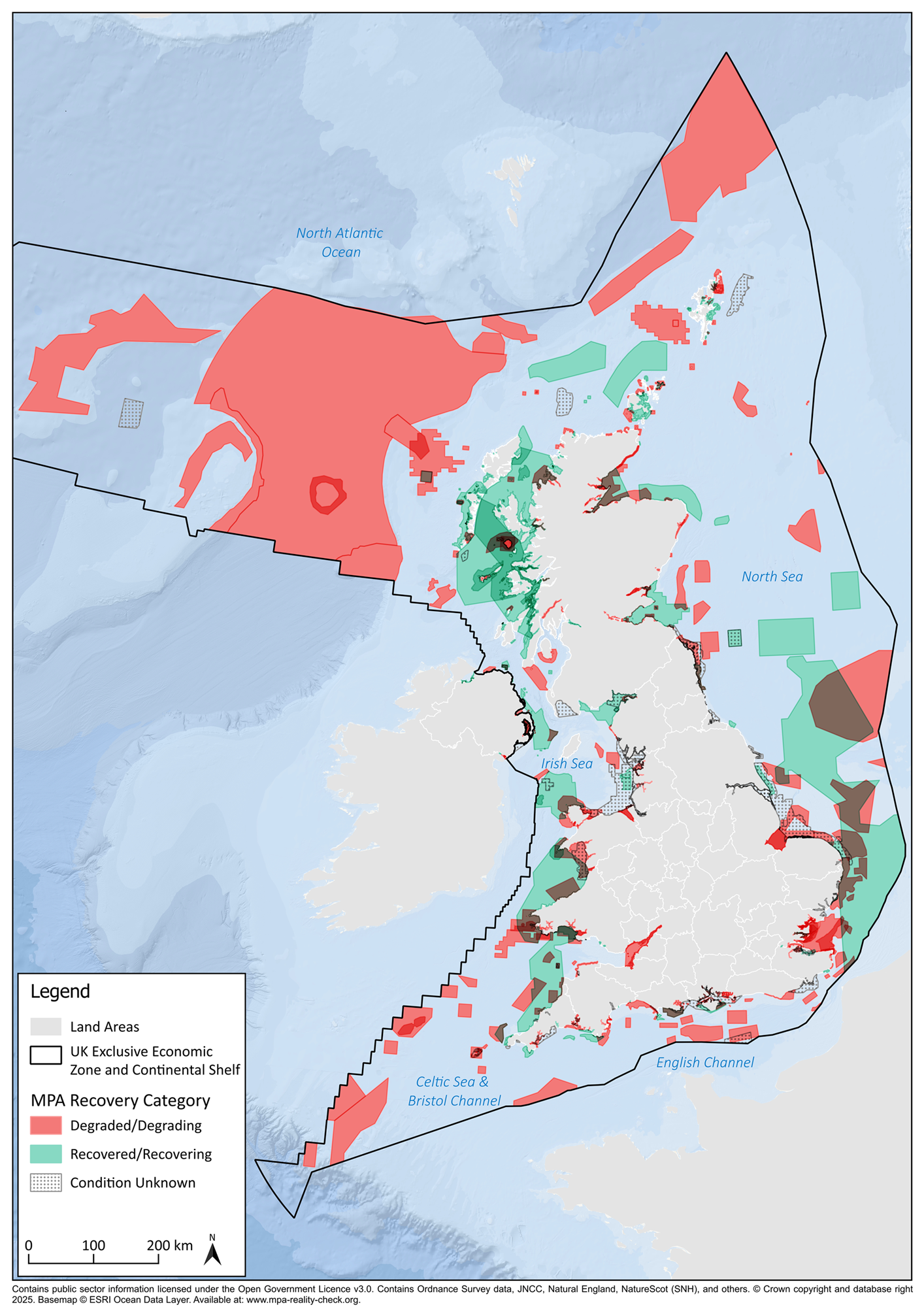

A standardized methodology was applied to categorize each MPA into a recovery category, with the aim of creating a colour-coded map which quickly shows the state of UK MPAs and can be easily interpreted by all: members of the public, MPs, NGOs, academics, industries, and so on, with more detailed information provided for each MPA for those who wish to take a deeper look.

The categorization method was simple—following a one-out-all-out, precautionary rule:

If one or more of the MPA’s features were thought to be in unfavourable, favourable declining, or destroyed condition, the MPA was categorized as Degraded/Degrading and colour-coded red.

If all of the MPA’s features were thought to be in favourable condition, the MPA was categorized as Recovered/Recovering and colour-coded green.

If no condition or vulnerability assessment or General Management Approach information was available for all of the MPA’s features, or some of the MPA’s features were thought to be in favourable condition but some had not been assessed, the MPA was categorized as Condition Unknown and colour-coded grey.

The results paint a worrying picture (Fig. 1). Fifty-six per cent of MPAs in the UK are categorized into the Degraded/Degrading category, just 28 per cent are in the Recovered/Recovering category, and 16 per cent fall into the Condition Unknown category.

Figure 1. The Wildlife Trusts Marine Protected Area Recovery Check Assessment (2025). Available at: www.mpa-reality-check.org

Undertaking this work highlighted that there is a significant lack of up-to-date data on the condition of UK MPAs. At the time of writing, we estimate around 49 per cent of marine features do not have a condition or vulnerability assessment. A General Management Approach is available for the majority of these, but these are often from when the MPA was designated, making them at risk of being out of date. Of those marine features with condition or vulnerability assessments, around 35 per cent are over 6 years old and around 11 per cent are over 10 years old.

Due to a significant lack of recent data, all condition or vulnerability assessments, and General Management Approaches were included in our assessment, no matter the date they were determined or their reported confidence. If this had not been done, the assessment would have been based on very little information, categorizing most MPAs as Condition Unknown. The assessment, therefore, is based on the most recent available information, recognizing that this may be considerably dated. We also recognize that monitoring is from an affected baseline following decades of industrial activities which impacted our seas before a true understanding of the baseline natural condition was understood.

The continued monitoring of MPAs is essential to ensure the appropriate management measures are in place to enable nature to recover. As shown by this assessment, it cannot be assumed that marine life is protected or recovering because it is within an MPA.

Similarly, the categorization of MPAs as Recovered/Recovering in our assessment does not mean that continued or additional management measures are not required. Nor does it indicate that this condition is expected to persist in the future, given ever-changing threats such as climate change, invasive non-native species, and the expansion of offshore renewable energy installations, as well as unforeseen threats.

An ageing evidence base

Increasing funding cuts to SNCBs responsible for the monitoring of MPAs means they are struggling to undertake this vital work and there is a significant risk of an ageing evidence base—evidence which is essential for determining and ensuring appropriate management measures are in place and for measuring the success of MPAs against targets. Accordingly, we ask: how can we support SNCBs in undertaking this work? Can we raise the importance of such work with the ministers responsible? Can we ensure the data we are already collecting in the wider marine sector is being used to help monitor MPAs? How can we come together to help plug evidence gaps?

Questioning the feature-based approach to MPA management

As shown by this assessment, the often-stated statistic of 38 per cent of our seas being within MPAs is not a suitable measure of effective management or recovery. The majority of MPAs are not managed by a whole-site approach. The continued application of the feature-based approach means that MPAs are only managed and monitored to protect the specific designated features within their boundaries. Anything else within the site is not protected and may or may not benefit from the designation. The Wildlife Trusts have long questioned the feature-based approach, since it fails to recognize the crucial ecological links between the protected features and their environment. For example, harbour porpoise Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) cover large areas, but are only designated to protect this one species. Similarly, the Falmouth to St Austell Bay Special Area of Protection (SPA) is designated to protect three seabird species, but the significant irreplaceable maerl habitats found within the MPA’s boundary are not protected, despite their ecological importance in supporting the food source these birds rely upon. As a result, trawling has been allowed to continue within the site, with negative impacts on the maerl.

Since the available data is for features only, our MPA Recovery Assessment can only reflect the condition of MPA features and is therefore not an area-based assessment of everything within the MPA. Similarly, it cannot be used to assess against 30x30 targets.

A wake-up call for MPA management

This analysis did not look at the cause for each condition assessment (for which readers should delve into the SNCB advice for individual MPAs), but it is hoped that the results will act as a wake-up call for those involved in managing MPAs. For example, we have failed to follow the mitigation hierarchy and avoid developing within MPAs. Seventy-three per cent of current offshore wind farm arrays overlap with at least one MPA. As reported by Natural England’s pilot project, which looked at the impact of developments on a few MPAs in the North Sea, this has resulted in some features being irreversibly damaged by developments. Additionally, condition assessments published by Natural Resources Wales earlier this year highlighted the impact of nutrient pollution on coastal MPAs. We need to do more to effectively protect and recover MPAs in the UK. The MPA Recovery Assessment will be updated periodically as new condition assessments are published, and it is hoped that, with time, the MPAs on this map will all turn green.

• Daniele Clifford (dclifford@wildlifetrusts.org) Marine Conservation Officer, The Wildlife Trusts.

www.linkedin.com/in/daniele-clifford

@thewildlifetrusts

The Wildlife Trusts’ MPA Recovery Check Assessment is available as an interactive map, along with supporting information here.

The MPA Reality Check website, which includes The Wildlife Trusts’ MPA Recovery Check Assessment, is currently a joint initiative between the Marine Conservation Society, The Wildlife Trusts, and Blue Marine Foundation. It is maintained by Marine Mapping Ltd.