Resetting our values towards nature

Above: Paul Rose with his black-tipped shark friends at Aldabra, Seychelles. Image © Manu San Félix.

That first dive, Easter 1969 at Chesil Cove on the English Channel coast, was the making of me. I knew nothing about science or conservation and the only thing I knew about the ocean, as it poured into my home-made wetsuit, was that it was cold, vast, unexplored and brought me a sense of freedom I had never previously experienced.

Not much has changed. The ocean remains our largest, most influential, least understood, and least protected ecosystem. What has changed is our understanding of how we have affected the ocean. My grandfather would have laughed at this. He always told me not to worry about the sea as, in his words, it cleans itself. The tide comes in, picks up any rubbish and takes it away, and, by tumbling the pebbles the waves clean the black sticky tar from the beach. He loved all of nature and to him the unfathomable size and power of the sea were proof that we could not possibly affect it, let alone overfish, pollute, and warm it up to an extent that our very existence could be called into question.

One fine day my colleague Dr Enric Sala, who was at the time a Professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, realized that ‘every science paper he wrote was like writing the obituary of the ocean’. We all know there are many ways to tackle the stresses we put on the ocean, and for Enric, cataloguing the decline was no longer an option. He had just read about Mike Fay’s megatransect expedition in which he walked over 3,000 kilometres across the Congo Basin. Then, in partnership with the President of Gabon, Omar Bongo, he helped to establish 13 new national parks. Mike’s expedition was funded by National Geographic and so Enric beat a path to their door, proposing to find, explore and help to protect the ocean’s last pristine places. They liked him and the idea, said they could support it if he raised most of the money, and he promptly left academia, joined National Geographic and started Pristine Seas1[1].

Groupers, Oeno Atoll, Pitcairn Islands. Image © Enric Sala / National Geographic.

Groupers, Oeno Atoll, Pitcairn Islands. Image © Enric Sala / National Geographic.

Mike Fay not only provided the inspiration, but also became the Pristine Seas Botanist. My role in Pristine Seas is Expedition Leader, and while we are at sea Mike is making cross-island or coastal transects so that we can connect our marine science to land ecosystems. It is a real treat to join Mike ashore for a day of surveys: he is one of those scientists who studies everything, is fun and informative, and moves with a purpose—making it appear that he is moving slowly when in fact he is almost impossible to keep pace with, particularly through mangroves.

We are a big team and can react quickly when it is necessary to do so, but the ideal situation is a year or two of lead-time. Expedition planning starts by analyzing the scientific case and political opportunity of each new target area and then working with our host-country scientists and community partners to develop a suitable approach. Doing this remotely works well, but it is not as much fun as all of us being together with a stack of maps and yellow sticky notes.

A Pristine Seas ship is a dream of mine, but practicalities dictate that we charter vessels of all kinds. The Argo, based in Costa Rica, is one of our smallest but also a firm favourite, as she is perfectly set up for diving and media work, and is home to the excellent DeepSee submarine. At the other end of the scale is the RRS James Clark Ross, which we chartered for our Ascension Island expedition from my old base camp, the British Antarctic Survey. The JCR enabled us to complete swath bathymetry and bio-acoustic surveys of seamounts, and to deploy plankton nets and bottom trawls. She was also a great platform for our drop-camera and pelagic camera rigs. It was an absolute delight to be back on board—but there was no diving on that expedition, which I found tougher to handle than I expected.

The Drop Cameras which will go to full ocean depth (and back!). These BRUV units contain a video camera and carry a bait canister. Image © Paul Rose.

Paul Rose with grouper in the outer islands of the Seychelles. Image © Manu San Félix.

Paul Rose with grouper in the outer islands of the Seychelles. Image © Manu San Félix.

Once the ship charter is arranged we form a team of between 12 and about 30 people, made up of our hosts and our permanent team of scientists, engineers, and filmmakers. After years of planning, the expedition becomes real once we start loading the ship. It’s a well-prepared routine: the compressor, dive chamber, oxygen, and dive gear are set up and commissioned. The Zodiacs, engines and all workboat support gear are positioned early. Drop-camera and pelagic camera rigs are also bulky and we get these workspaces allocated promptly, whilst at the same time finding space for the topside and underwater film teams and their vast amounts of kit.

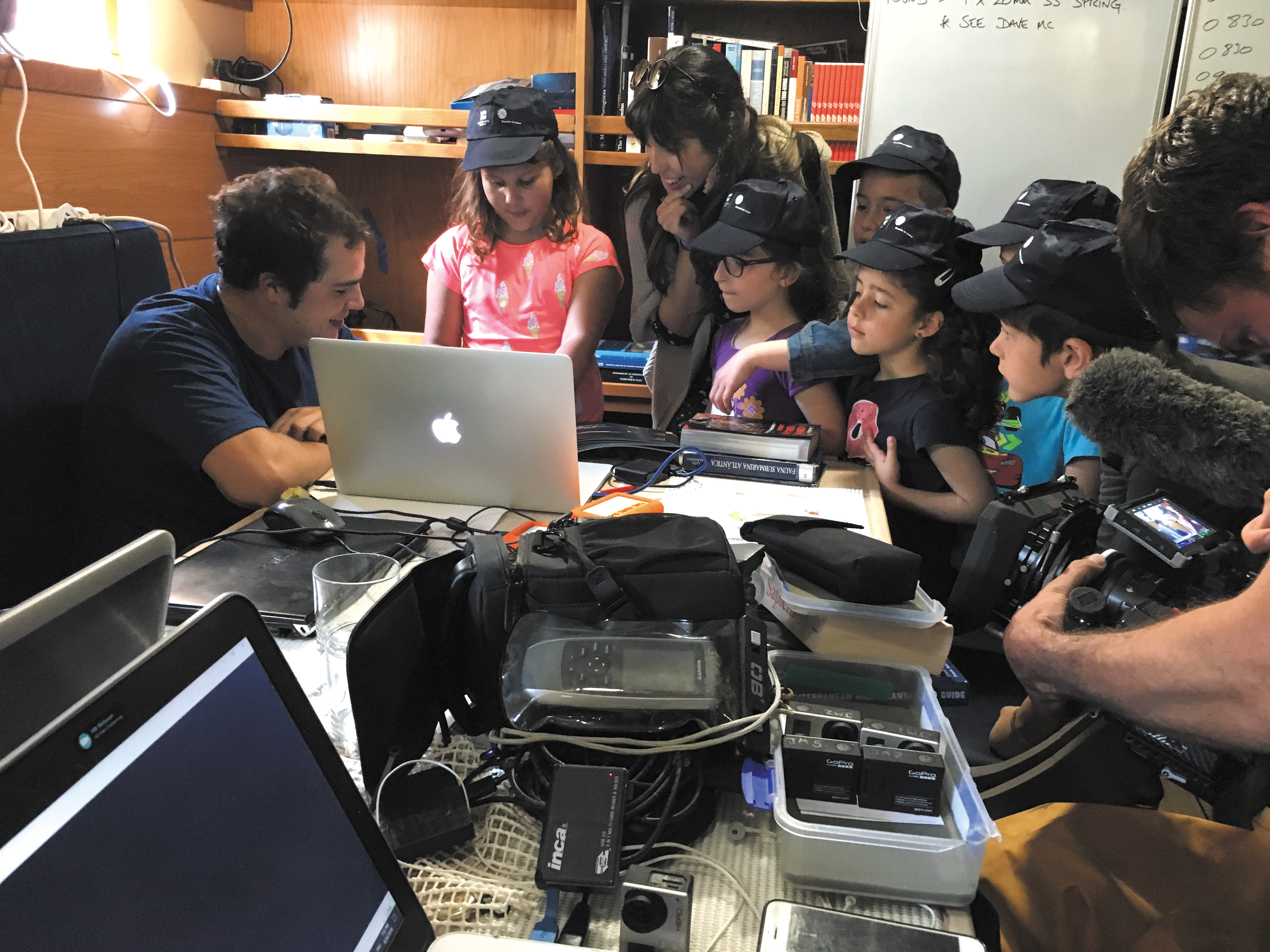

Schoolchildren visiting the team on the Azores expedition. Image © Paul Rose.

Then at last there is that moment seagoing researchers know so well: we’re all aboard, the gear is commissioned, stowed and made ready for sea. We’ve done it—the expedition is a living, breathing, beautiful thing! What a moment. I love this—the lines are slipped and we are off to sea. Even writing this is an emotional experience.

Images: Top left: A Galapagos sea lion chases a large school of Salema fish off Isabela Island, Galápagos Islands. Image © Enric Sala.

Top right: Healthy corals form a lush layer over Palau’s sea floor, providing home to an array of fish and invertebrates, such as these blue starfish (Linckia laevigata). Image © Enric Sala.

Since Pristine Seas was launched in 2008, we have carried out 30 expeditions, created 22 marine reserves, in which over 5 million square kilometres of ocean are protected, and published 112 science reports.

The numbers alone tell a good story but I also cherish the friendships we have made along the way, through the pre- and post-expedition community conferences, and the Explorer Classroom sessions. We communicate live with thousands of schoolchildren all over the world. It’s terrific to share our work live from the sea.

This has been our life and the strategy has worked well, but now, of course, we have another factor to consider. All of our targets and the related travel must be re-evaluated in the post-COVID-19 recovery period. We will not be travelling until there is a vaccine, and these past months have been a period to enjoy a longer lead-time for planning, to write up those reports, learn new skills (such as being a semi-professional ‘zoomer’), develop long-term approaches to ocean protection, and—fingers crossed—get ready for being at sea sometime in 2021!

Aside from buying a green screen to enable virtual backgrounds to hopefully raise the standards of my zoom sessions, there have been other benefits of this extraordinary period. The most exciting to see are the headlines about our relationship with nature. At last, science leads the news and the value of scientific data and evidence has never been more recognized. With trust in political leadership, and the motivations and ethics of business at an all-time low, we can still have faith in the indisputable accuracy and beauty of scientific field data. Even the ropiest press outlets are reporting that the COVID-19 crisis has been caused by humans being out of balance with nature, and that the only true ‘vaccine’ against further pandemics is to restore that balance.

What has emerged is a very simple message: the health of everyone on the planet is reliant on everyone else’s health, which in turn, is reliant on nature. The motivation for doing the right thing couldn’t be better.

COVID-19 has shaken up news reporting, and smart decision-makers are on board with the need to protect nature. The 30 x 30 campaign2 is now a truly global ambition. Even better, 30 per cent is now seen as a waypoint to the 50 x 50 goals as set out in E.O. Wilson’s Half-Earth3. We have been helped by the recent report that the benefits of protecting 30 per cent or more of the planet outweigh the costs by a ratio of at least 5:14, and that nature conservation is smart business—driving economic growth and contributing to a resilient global economy. Oh, and by the way, it will keep us alive too.

These feel like revolutionary times and represent the best opportunity we have had in recent history to reset our values towards nature. COVID-19 really can be the catalyst for change: we will protect what we have, restore what has been damaged and reset our values to prevent it happening again. There is no time to lose, so when it comes to our values I have my list ready:

1. We need to be close to nature through all of our formative years. The best way to do that is to have every subject always taught outside of the classroom.

2. Activities that bring young people close to nature such as scuba diving, sailing, camping, climbing, skiing, cycling, should be available in all schools. These activities are the best way to learn and there is no excuse for them only being available in the private school system.

3. Before a politician takes office, a business leader accepts a boardroom position, or a community influencer accepts their role, they must be transparent about their values by proving their record of fieldwork, charity efforts, humanitarian, arts, social, sports activities, and their relationship with nature. Just giving financial support is not enough; records must show real hands-on life-defining efforts.

4. To help us become better-informed consumers and to encourage or force better-informed business decision-making, all businesses must be transparent about their values. Before any purchase, it should be routine for us to question the company’s values, especially for big purchases such as mortgages, insurance, investments, vehicles, and so on.

5. The way we vote can easily change to reflect these values. I imagine election forms that clearly display the candidate’s values. If voting online, the values section would flash red if none were shown: ‘Danger, danger. The candidate you are about to vote for has not demonstrated any values!’.

6. We must have enforceable international environmental law. There is progress here and I am hopeful that in the next few years we will see certain politicians and business leaders behind bars at The Hague for crimes against humanity and the environment.

Paul Rose joining with the surf lifeguards as part of his Coastal Path BBC documentary. © Jo Horsey.

If this six-step values plan works then it won’t be long before we see politicians and business leaders with ‘that look’; you know, the indefinable energy and inner glow that people have after an exciting time in, on, or under the sea. Then I can see a future where: politicians are connected to the sea; illegal fishing comes to an end; scuba diving is taught in all schools; education puts nature first. In short, a values-based society.

Paul Rose

www.paulrose.org

[1] 1 https://www.nationalgeographic.org/projects/pristine-seas/