The evolution of ocean literacy

Throughout history, the ocean has acted as a connector across time and space, providing trade routes and transport, supporting multiple industries, and providing for coastal communities—and those further inland—for generations. But for too many people, their relationship with the ocean stops where their feet touch the sand or on the clifftop as they look out towards the horizon. This lack of connection with the ocean has spurred a growth in marine social science research that seeks to better understand the complexity of the many different relationships people may have with the ocean, coasts, and seas, but also to understand what the barriers to those relationships might be and how connections could be fostered.

In January 2021, the UN launched the Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, which clearly sets out its aspirations to recognize the breadth of ocean science and research, ranging from the traditional natural and physical sciences to social sciences, arts, and humanities. Crucially, it recognizes diverse knowledges and values, including involvement of local and indigenous communities who are central to ocean management. Among the 10 Ocean Decade challenges is an aim to ‘change humanity’s relationship with the ocean’, with enhancing ocean literacy positioned as the way in which this change will be realised. But what is ocean literacy?

Ocean literacy: an introduction

At its simplest, ocean literacy can be described as an understanding of your influence on the ocean, and its influence on you, and is underpinned by seven key principles (Box 1) co-developed in the USA by a community of ocean scientists, educators, and policy makers in the early 2000s. Ocean literacy was initially aimed at school-aged students, and the seven principles sought to increase the students’ knowledge, in order to encourage ‘better’ ocean decisions. The principles provided a guide for what students should know on completion of secondary-level education. Since then, several ocean literacy initiatives have developed, including the National Marine Educators Association in the USA (NMEA), the European Marine Science Education Association in Europe (EMSEA), the All-Atlantic Blue Schools Network (AABSN), and the International Ocean Literacy Survey (IOLS).

Box 1 – Seven principles of ocean literacy (developed and adapted by the NMEA).

- Ocean Literacy Principle 1: The Earth has one big ocean with many features.

- Ocean Literacy Principle 2: The ocean and the life in the ocean shape the features of the Earth.

- Ocean Literacy Principle 3: The ocean is a major influence on weather and climate.

- Ocean Literacy Principle 4: The ocean made the Earth habitable.

- Ocean Literacy Principle 5: The ocean supports a great diversity of life and ecosystems.

- Ocean Literacy Principle 6: The ocean and humans are inextricably interconnected.

- Ocean Literacy Principle 7: The ocean is largely unexplored.

By developing understanding of the seven ocean literacy principles, it was thought that an individual would become ‘ocean literate’ in three dimensions, and would be able to:

- Understand fundamental concepts about the ocean (Knowledge);

- Communicate in a meaningful way about the ocean (Communication);

- Behave responsibly towards the ocean and its resources (Behaviour).

The evolution of ocean literacy

In recent years, ocean literacy has moved away from its education origins, taking into account the multiple factors that may influence someone’s understanding of how they might influence the ocean, and vice versa.

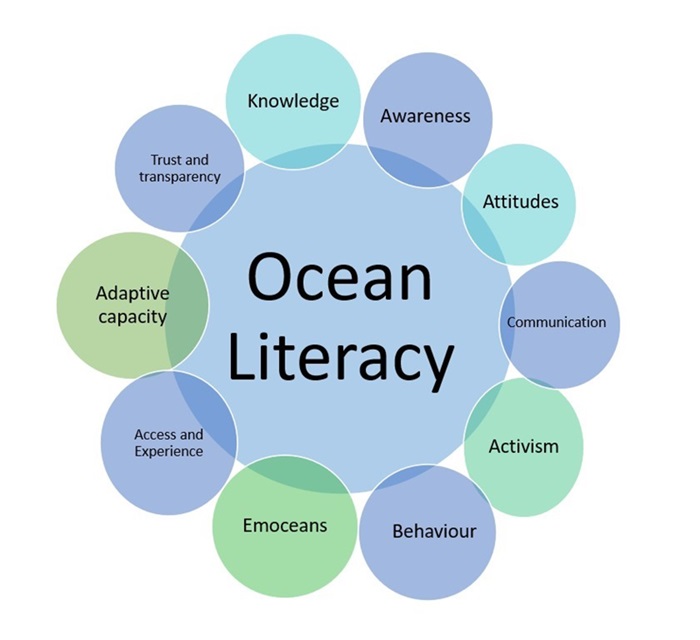

Recent research has introduced the dimensions of Awareness, Activism and Attitudes, and a UK review funded by Defra explored other relevant concepts including pro-environmental behaviour, public perceptions research, and marine citizenship. This resulted in 10 proposed dimensions of ocean literacy, including four new dimensions and an expansion of the previously accepted dimensions (See Fig. 1 & Box 2). While the original dimensions remain critical, the concept is increasingly understood as being about the relationships between people and the ocean, coasts and seas. Importantly, this is not limited to coastal areas: contemporary discussions about ocean literacy recognize its potential for connecting everyone to the ocean, regardless of location. This evolved framework recognizes the challenges that might prevent physical access or experience of the ocean or coast, and that connection to these environments can be through art, literature, documentaries such as Blue Planet II, or technology such as virtual reality.

Figure 1. The ten dimensions of ocean literacy (McKinley et al. 2023).

Box 2 – The 10 proposed dimensions of ocean literacy (summarized)

- Knowledge is what a person knows about an ocean-related topic and the links between topics.

- Awareness is the basic knowledge and understanding that a situation, problem, or concept exists.

- The dimension of Attitude is related to a level of agreement with, or concern for, a particular position.

- Behaviour relates to decisions, choices, actions, and habits with respect to ocean-related issues at a range of scales.

- Activism is the degree to which a person engages in a wide range of activities, which can constitute activism—such as campaigning—to bring about changes in policy, attitudes, behaviour, etc.

- Communication as a dimension of ocean literacy includes:

- the extent to which a person communicates with others on ocean-related topics.

- how people get their information about ocean issues—and what communication works.

- how institutions communicate to different audiences about ocean issues.

- Emoceans is about how a person responds emotionally when they think about, are near/within, or consider issues relating to, the ocean.

- Access and experience relate to a person’s real or artificial (through virtual reality, for example) ocean experiences. Barriers to ocean access and experiences should also be considered.

- Adaptive capacity refers to a person or community’s capacity to adapt and respond to changing conditions relating to their ocean (e.g. climate change).

- The dimension of Trust and transparency: the level of trust someone places in sources of ocean information, knowledge and decision-making, and their perception of how transparent these are.

The 10 dimensions are available in full at: www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X22011493

Measuring ocean literacy

While there is no agreed way of measuring ocean literacy, projects that provide a starting point include the International Ocean Literacy Survey, as well as assessments in Canada, through the Canadian Ocean Literacy Coalition, and in Brazil. In the UK, Defra, Marine Scotland, Natural Resources Wales, and the Ocean Conservation Trust funded a UK-wide ocean literacy assessment. This provided valuable insights into the relationships communities have with their marine and coastal environment, including their concerns, what they value, their ocean experiences, and how they feel about the ocean.

Integrating values into management

The integration of different disciplines (e.g. social science) and diverse values into marine management is an Ocean Decade global science priority. In the UK, the Diverse Marine Values project is using a range of approaches including arts-based and social science methods to understand how the communities of Portsmouth, Shetland, and Chepstow value the coast and sea. Working closely with decision-making organizations, the project will develop guidance for improved integration of different types of values (e.g. economic, ecological, social, cultural) into UK marine management and decision-making.

What’s next for ocean literacy?

Established in 2021, the Ocean Literacy Research Community aims to bring together researchers and practitioners from around the world to co-develop an ocean literacy research agenda for the future. This includes developing how we measure ocean literacy, and how it can be operationalized to support other key ocean issues such as climate change, the blue economy, and sustainable coastal communities.

• Dr Emma McKinley (McKinleye1@cardiff.ac.uk)

Senior Research Fellow, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Cardiff University.

Further reading

McKinley, E.,Burdon, D. and Shellock, R.J. 2023. The evolution of ocean literacy: A new framework for the United Nations Ocean Decade and beyond. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114467

Ocean Literacy in England & Wales. Headline Findings Report. Defra. https://oceanconservationtrust.org/app/uploads/15131_ME5239OceanLiteracyHeadlineReport_FINAL.pdf

OceanLiteracyGuide_V3_2020-8x11-1.pdf (unesco.org)

Understanding Ocean Literacy and Ocean Climate Related Behaviour in the UK https://weareocean.blue/resource/understanding-ocean-literacy-and-ocean-climate-related-behaviour-in-the-uk/