Unfurling isopod evolution

I’m evolutionary biologist Jessica Thomas Thorpe and my research is re-writing the isopod family tree; I study these incredible crustaceans to understand how they have adapted to almost every environment on Earth.

Early interest in isopods

As a child, I remember hunting for woodlice in my parents’ garden in the south-east of England. I would spend hours captivated by these little creatures, which are common across UK gardens, but especially the type we’d call ‘pill beetles’ or ‘pill bugs’ (so called for their sudden resemblance, if disturbed, to old-fashioned pills rolled in silver). Now, I study woodlice, which are part of a group called Isopoda. Isopods are crustaceans, so woodlice are more closely related to crabs and lobsters than other terrestrial creepy-crawlies such as insects, spiders, or millipedes. As part of a global network of isopod researchers, I study the DNA of all types of isopod, from those found in my childhood back garden, to the deep sea, and everywhere in between.

I’ve always been fascinated by natural history, but my first interest in studying evolution came from a book my father gave me on the science behind Jurassic Park. He explained how DNA split apart to replicate, and not long after, I decided to study genetics at university. My subsequent PhD in molecular evolution found me working on insect evolution, and this was followed by a stint in ancient DNA, sequencing the mammoth (more Ice Age than Jurassic Park). However, when it came time to turn my scientific skill set towards independent postdoctoral research, my long-term interest in evolution and the mini-beasts in my childhood back garden came full circle.

Evolutionary transitions and adaptations

If we were to step back in time 400–500 million years, we would find life predominantly in the sea; plants and animals (such as insects) had only just started to evolve and adapt to life on land. Marine isopods first appear in the fossil record around 300 million years ago, but isopods transitioned to life on land much later; the first terrestrial isopod fossils appear just over 100 million years ago. Isopods now inhabit almost every environment on Earth. I am studying their transition to terrestrial life, alongside other ecological transitions: for example, shifts to freshwater and deep-sea habitats as well as parasitism, using DNA to investigate their evolution.

Land-dwelling woodlice and their relatives, sea-slaters, which live on the edge of the land and sea, share several key adaptations to terrestrial life. Both have water-resistant cuticles and water transport systems (and drink through their legs). Some terrestrial isopods (such as the pill bugs) have evolved quite complex lungs from organs which ancestrally were gills. Isopods have also developed behavioural skills to avoid water loss: conglobation—meaning they can roll up into a ball, and aggregation—piling up together. But at the molecular level, what sorts of changes have enabled their adaptation from aquatic to terrestrial life? This is one of the questions I am trying to answer as part of my research.

In order to study isopod evolutionary transitions, I’m working with other experts to collect a wide range of isopod species from around the world. Many of my samples have come from the south-west of the UK, close to the Marine Biological Association’s laboratory. Others have come from as far away as Australia, Antarctica, and the deep sea. It’s been very exciting working with isopod researchers from all around the world—the community has been exceptionally generous in providing specimens for DNA analysis (Fig. 1).

Sampling UK isopods with the Darwin Tree of Life project

I carry out my research at the Wellcome Sanger Institute which, alongside the Marine Biological Association, is a partner in the Darwin Tree of Life project. The project aims to sequence the genomes of all 70,000 species of plants, animals, and fungi in Britain and Ireland. It is a collaboration between the fields of biodiversity and genomics, aiming to transform biology, conservation, and biotechnology. The Darwin Tree of Life project is affiliated with the Earth BioGenome Project, an initiative that aims to genetically catalogue all life on Earth. My isopod research fits within these remits, so all the genome sequencing I am carrying out as part of my Janet Thornton Fellowship will contribute to the Darwin Tree of Life and Earth BioGenome projects.

I have been out searching for and sampling UK isopods in the south-west of England with local experts and researchers from the Marine Biological Association. This area has the highest marine isopod biodiversity in the UK, and we’ve collected a wealth of samples for genome research.

Molecular data and evolutionary trees

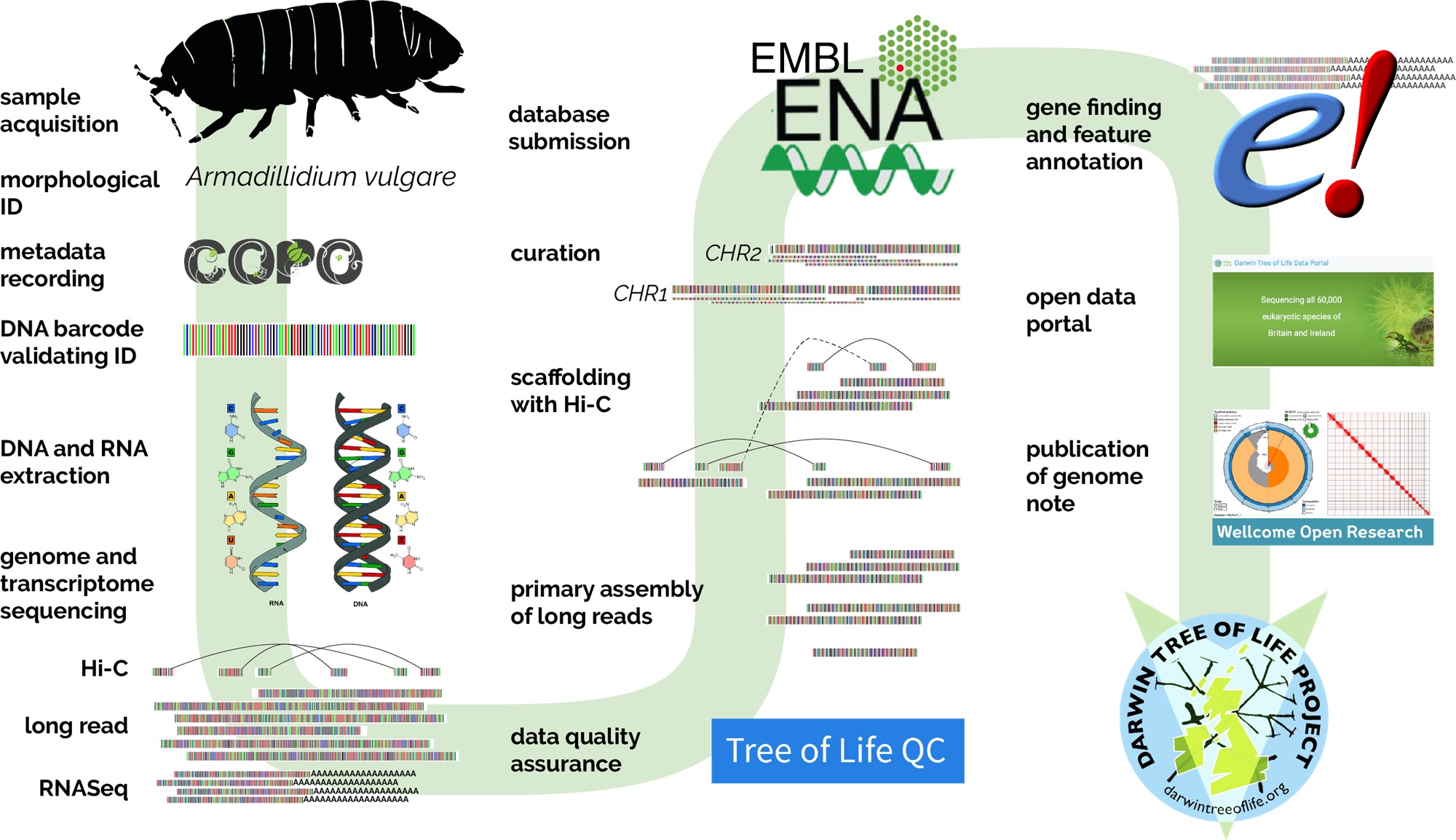

The process of building an evolutionary tree starts with sampling and extracting the DNA of an organism, but there is a long ‘pipeline’ of steps to get to a complete genome. The genome assembly pipeline that makes up the Darwin Tree of Life project is a complex tour de force that can accommodate a huge variety of organisms. Summarized in the figure below, the process involves many different teams of experts at Sanger.

My expertise now lies in analysing these isopod genomes, which begins with using the genes to create a phylogeny—a sort of large-scale family tree—of isopod species. Examining what’s in the genomes, and how they have changed over time, will enable me to learn all about the evolution of these fascinating creatures and their adaptation to life on land.

The first isopod genomes have just been released, as has my research paper entitled ‘Phylogenomics supports a single origin of terrestriality in isopods’. There are more publications coming soon, so watch this space!

Dr Jessica Thomas Thorpe, Janet Thornton Fellow, Wellcome Sanger Institute.

www.sanger.ac.uk/person/thomas-thorpe-jessica

portal.darwintreeoflife.org

More about the Janet Thornton Postdoctoral Fellowship: www.sanger.ac.uk/about/equality-in-science/janet-thornton-fellowship

Further reading

Thomas Thorpe, J.A. 2024. Phylogenomics supports a single origin of terrestriality in isopods. Proc. R. Soc. B. 29120241042 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2024.1042