Main image: The sea in the resort village of Zaliznyy Port in the Kherson region, southern Ukraine.

Грибюк Руслан Володимирович, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

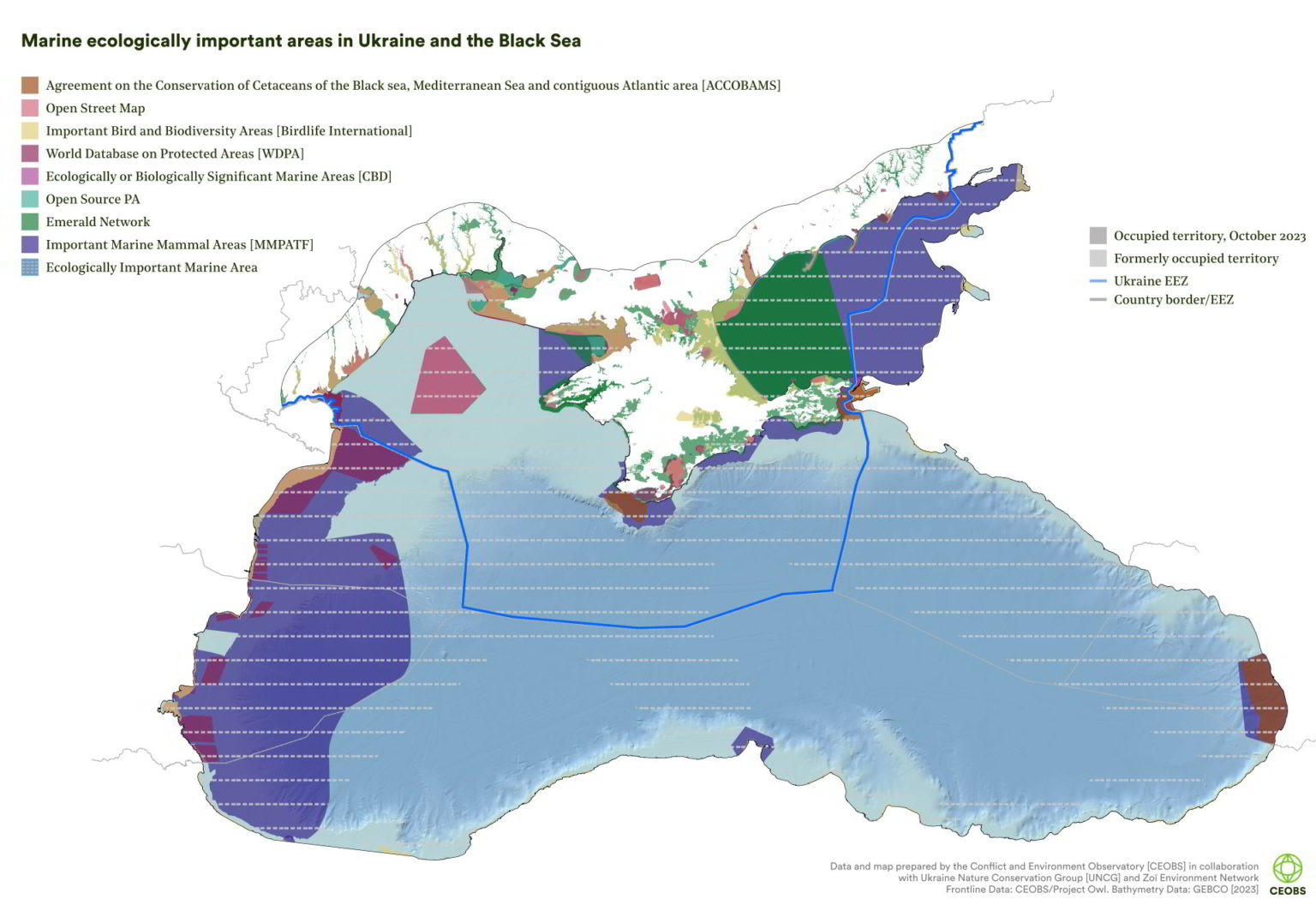

The Black Sea and the Sea of Azov host a kaleidoscope of unique coastal and marine habitats, including estuaries, lagoons, islands, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows, which are home to hundreds of rare species.1 Both seas are strategically2 central to the war3 and, due in part to their already degraded state, may be severely impacted by it. Key marine species are now at risk in vulnerable areas due to the shift from cooperation and conservation to full-blown conflict4 (Fig. 4).

The Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOBS)5 highlights and maps the spiralling war impacts in terms of chemical and acoustic pollution, habitat disruption, fisheries, and shipping. The Ukraine War Environmental Consequences Group (UWEC)6 similarly outlines known and likely impacts. It lists damage to coasts, reserves, and parks as well as impacts on underwater marine ecosystems (Box 1).

The destruction of the Kakhova dam (Box 2)7 and its 2,092 km2 reservoir in June 2023 highlighted the downstream impacts of the war from the Dnieper and other vast river basins feeding into the Black Sea. As the war continues, the risk of other major events is high, additionally pushing back Sustainable Development Goals in social and biophysical terms (Fig. 1).

Box 1. Land and sea: clear risks as war impacts emerge.

Underwater marine ecosystems: risks arise from sunken ships and missiles, anchor usage, and munitions explosions. Pollution may outweigh the benefits of artificial reefs. Some of the greatest biological diversity is concentrated in benthic seagrass or algal communities at risk.

Figure 2. A dead cetacean in Tuzlovsky Limany National Park in Ukraine, June 2023. Image courtesy of Ivan Rusev.

Marine mammals: dolphin mass mortality has been noted from start of sea-based hostilities in March 2022. White-sided dolphins have washed ashore (Ukraine/Turkey). Dead and disoriented dolphins with wounds and extensive burns have been recorded (Bulgaria/Romania). Much is likely to remain unknown due to areas being off-limits.

Sonar: explosions and sonar from warships and submarines’ echo-location affect dolphin hearing, behaviour, and ability to survive.

Invasive species: unmonitored vessels can bring non-native invasive species, e.g. by the discharge of ballast water. In the early 1980s, the Atlantic comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi significantly impacted the Black Sea ecosystem and anchovy stocks.

Birds: Azov-Black Sea coasts host many European bird species, which face habitat, nesting, and migration disturbance. Wetland birds recently thrived on sand spits on the Azov coast and the Meotida National Nature Park (2009). They are now at risk. Biodiversity was lost when the war came to Kryva Kosa Spit in 2015.

Pollution: the sinking of warships, aircraft, and other military equipment can lead to oil spills toxic to marine life, and can poison the marine environment for decades. Cluster bombs add to such risks. Surveys take a long time.

Military equipment: movements, mines, and fortification destroy soil and vegetation, and wreck coastal marine habitats. Biotopes in the swash and surf zones, containing unique biodiversity among the sand and strandline, may also be damaged during coastal minelaying, explosions, and sand mining from beaches for use in building fortifications.

Infrastructure destruction: factories, bridges, dams and other sources of land, river, and sea contamination have the potential to affect futures generations. Material and toxic releases affect biodiversity and public health.

Military training: the Opuk Nature Reserve has been used as a training ground. Bombing, military equipment movements, detonation of acoustic bombs in the sea, and troop landings during Russian military exercises have all impacted local coastal, steppe, and estuarine habitats. Cluster bombs add to risks of downstream impacts.

Fires: vast, unchecked fires have raged across many areas, affecting reserves in coastal areas of the Mykolaiv and Kherson regions, including the Back Sea Biosphere Reserve, Lower Dnipro National Nature Park, and the Kinburn Spit Park.

Coastal conservation: the conflict has affected the fabric and management of protected areas and water bodies. Plans for Marine Protected Areas and other works are on hold (Box 2).

Source: Ecoaction Climate Program https://uwecworkgroup.info/war-and-the-sea-how-hostilities-threaten-the-coastal-and-marine-ecosystems-of-the-black-and-azov-seas/

Impacts on an ecologically degraded sea

Headline media stories8 about militarized and stranded dolphins, naval sea drones, and missile threats to beach tourists may have raised public awareness of coastal impacts of war in 2023, but the deeper impacts on sea life and ecosystems will take time to surface.

Around 87 per cent of the Black Sea water is naturally anoxic, so even in normal times it is highly sensitive to anthropogenic impacts. These are substantial: from 170 million people in 17 countries living within the river catchments that feed around 350 km3/year of water into what is an almost landlocked basin. The Black Sea Commission9 outlined the sea’s known pre-conflict status and challenges: pollution by land-based sources; losses of biodiversity because of pollution, invasive species, and the destruction of habitats; and overexploitation of marine living resources leading to a collapse of fisheries, with significant impacts on the ecosystem’s health. The war impacts may add to these.

The Kakhova dam collapse alone added to pollution of the Black Sea, but the likely downstream impacts from affected areas and cities could potentially expand to include radioactive releases from nuclear power plants exploited for war ends, let alone the threatened use of nuclear weapons.

The conflict has cut marine traffic in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov and changed fisheries governance and control. Reductions in shipping can bring beneficial or negative effects, depending on routes, cargoes, ship management, and roles. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) says Ukrainian sea fishery fleets were inactive during 2022, with nearly all the total annual Black Sea and Azov Sea catches of 13,000 tonnes lost10. It remains unclear how stocks will respond to changes in fishing intensity and location. Inland and delta fisheries were also impacted, not least by pollution, direct blast damage, and eutrophication.

Figure 3. War crimes prosecutor. Source: Ukrainian Ministry of Justice.

Box 2. Downstream impacts of Kakhova Dam destruction on the Black Sea

The flooding and deposition of material and contaminants will have a significant impact on the provision of ecosystem services on land and at sea. This includes drinking water, groundwater supply and quality, wastewater treatment, recreation, renewable energy provision, and aquaculture.

General impacts: at the time of writing, UNEP was compiling a report on the impacts of the destruction of the Kakhova dam. UNOSAT suggest that approximately 620 km2 of land were flooded, hitting agricultural, residential, and industrial areas, and ecologically important habitats and military fortifications. Hazardous sites have been impacted and industrial facilities are likely to have released fuels and other pollutants. Other impacts come from sewage pits, petrol stations, landfills, and solid waste. The HALO Trust reports that mines and unexploded ordnance are likely to have been mobilized by the flood.

Six areas of ecological importance impacted by floodwaters include Ukraine’s Emerald Network sites; Lower Dnipro Delta, and a wetland of international importance (RAMSAR Convention).

Discharges to the sea may impact on seafloor habitats and the vulnerable Zernov’s Phyllophora Fields, in the north-western Black Sea. Reduced salinity could have impacted currents, water mixing, and productivity in the northern Black Sea, with plankton blooms increasing 100-fold by worst-case estimates. Specialists from the Odessa-based UkrSCES suggested that 40–50 per cent of these blooms were potentially dangerous due to the production of toxins.

Source: CEOBS https://ceobs.org/analysing-the-environmental-consequences-of-the-kakhovka-dam-collapse/

Data gaps in conflict

Researchers in conflict often resort to rough approximations using satellite imagery or other remotely sensed and fragmentary data, all of which has vastly improved in recent years. However, further research will be needed to determine the true impact of the conflict on the marine and littoral environment. Conservation plans for now are on hold (Box 3).

It doesn’t help that Ukraine’s research capacity has dropped, with around 20 per cent of universities physically damaged and around 10 per cent of Ukrainian scientists fleeing their country, according to Ukraine’s Ministry of Science and Education.11 The Ukrainian Scientific Center of Ecology of the Sea (UkrSCES) hopes to resume its work on the Black and Azov Seas and is looking for partners.12

Fishing and freedom of navigation in the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait, through which it connects to the Black Sea, were previously governed by bilateral treaties between Ukraine and Russia. The termination of fishery agreements during 2022 means that there is currently no joint management in the Sea of Azov. Its contested future now partly depends on future peace deals. Indeed, Ukraine’s division makes it hard to assess the state of the environment and progress under pre-conflict national plans and international treaties.

Environmental damage to land is often more apparent than for the sea, and measuring both is hard. Military pollution goes unreported, says the Paris-based Organisation for Economic and Cultural Development (OECD),13 as monitoring systems are disrupted or destroyed, so such damage accumulates. Ukraine has launched tools to document environmental war damage and crimes on land, including a data dashboard: ‘EcoZagroza’. The State Environmental Inspection is recording the many known crimes against the environment and cases of damage. The OECD reports that special units have been collecting evidence for tests and to evaluate compensation (see Fig. 2).

Such assessments in the marine environment will be long-term undertakings and difficult to achieve.14 The TUDAV Marine Research Foundation of Turkey, a NATO near-neighbour of Russia facing Ukraine across the Black Sea, is just one of the regional littoral states’ (Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Russia and Georgia) institutions that will be tracking the marine environment for direct and indirect impacts.15

Figure 4. Marine ecologically important areas in Ukraine and the Black Sea. Data and map prepared by the Conflict and Environment Observatory [CEOBS] in collaboration with Ukraine Nature Conservation Group [UNCG] and Zoï Environment Network. Frontline Data: CEOBS/Project Owl. Bathymetry Data: GEBCO [2023]

Box 3. The poor state of Ukraine’s degraded Black and Azov seas: marine conservation on hold

- Its geographical and physical characteristics make the Black Sea unusual. Ukraine alone has 2,700 km of coastline along the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.

- Ecologically important areas have been shrinking, with the small and valuable remaining areas continuing to be threatened. Ukraine’s coastal and marine ecological areas include 22 Ramsar Sites covering 750,521 ha, terrestrial Protected Areas (PAs), and 45 designated Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

- Ukraine has designated just 1.3 per cent of its total marine area as MPAs, and the status of that protection is poor. This has contributed to high levels of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing in the Black and Azov seas. Poor product traceability, and weak fisheries governance undermine conservation efforts. The annexation of Crimea cut Ukraine’s access to 11 MPAs in its coastal zone. Since February 2022, access to the marine components of two further PAs have been lost: Сhornomorsky Biosphere Reserve, and the Biloberezhia Sviatoslava national park (both in southern Kherson).

- Frustrated plans since 2016 to expand marine and coastal PAs include an expansion of the Karkinitsky Bay PA, and new MPAs along the Crimean coast and in the west of the Sea of Azov. These were expected in 2023, with 19 new MPAs expected along the Crimean coast of the Black Sea to give high protection to the ecologically significant Kerch Straits. Ukrainian conservationists have also proposed that the entirety of the western section of the Azov Sea — some 14,251 km2 — be designated as one continuous MPA.

Source: https://ceobs.org/ukraine-conflict-environmental-briefing-the-coastal-and-marine-environment/#3

If the fog of war lifts

Post-conflict recovery plans are under development to ensure a built-in green recovery. This depends on scientists returning—a majority say they will—and in the meantime them being supported in their work virtually, through funding or in placements abroad.

Various scientific organizations have suggested means of helping Ukrainian scientists—most prominently, the national academies of science of Europe (including Germany, Poland, Denmark, and the United Kingdom) and the US. Ukraine can count on support from the UN, EU, the Black Sea Commission, among others, should peace return. In 2021, The European Commission (EC) set up the Black Sea Assistance Mechanism (BSAM) to support the implementation of the Common Maritime Agenda for the Black Sea.

While some environmental and tourism plans are unaffected, stalled ones could be revived. Beyond the work of the Black Sea Commission, the OECD has previously underlined rapid progress after 2014 between Ukraine and the EU on many issues, including marine conservation.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has shaken the international governance system for biodiversity conservation and halted international scientific cooperation in important areas, notably the Arctic1. As the international community wrestles with implications beyond the war in Ukraine, the future of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov depends on whether Ukraine regains all its UN-backed 2014 borders, as well as direct or indirect diplomatic and environmental cooperation among all littoral states of these unusual16 regional seas, including Russia.

• Dr Matthew Bunce FMBA (matt.bunce@outlook.com)

Further reading

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/13/science/war-environmental-impact-ukraine.html

[2] https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/05/20/what-is-russia-doing-in-black-sea-pub-84549

[3] https://warontherocks.com/2022/04/the-russo-ukrainian-war-at-sea-retrospect-and-prospect/

[4] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0964569121003604

[5] https://ceobs.org/ukraine-conflict-environmental-briefing-the-coastal-and-marine-environment/

[6] https://uwecworkgroup.info/war-and-the-sea-how-hostilities-threaten-the-coastal-and-marine-ecosystems-of-the-black-and-azov-seas/

[7] https://ceobs.org/analysing-the-environmental-consequences-of-the-kakhovka-dam-collapse/

[8] https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20221222-how-the-war-in-ukraine-is-killing-marine-mammals

[9] http://www.blacksea-commission.org/

[10] https://www.fao.org/3/cc3370en/cc3370en.pdf

[11] https://theconversation.com/ukrainian-science-is-struggling-threatening-long-term-economic-recovery-history-shows-ways-to-support-the-ukrainian-scientific-system-207477

[12] https://sea.gov.ua/?lang=en

[13] https://www.oecd.org/ukraine-hub/policy-responses/environmental-impacts-of-the-war-in-ukraine-and-prospects-for-a-green-reconstruction-9e86d691/

[14] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0025326X9390038L

[15] https://tudav.org/en/from-us/press-releases/press-release-a-war-in-the-black-sea-and-its-effects-on-marine-environment/

[16] https://www.marineinsight.com/know-more/8-amazing-facts-about-the-black-sea/