Banner image: Walls of large fish that have reached reproductive age can be seen commonly in tropical areas where controls on over-exploitation are effective. This is one such area on Ningaloo reef, Western Australia. © Anne Sheppard.

Consider this: a dynamite fisherman on coral reefs in some south-east Asian countries can earn double the salary of a university professor from that country. Now, whatever you may think about university professors, this does illustrate the ease by which a few members from the country’s poorest sector can attain previously unimaginable wealth. The trouble is the activity leaves behind devastated and largely worthless areas of coral reefs that remain devoid of riches for several human generations. In other tropical countries, fishers use poisons, even DDT, to secure some protein from continually diminishing resources. In response to the obvious question of whether the DDT was harmful to those who ate the killed fish, the answer given was that, yes, of course, but not for several months perhaps, and he needed to feed his family that week.

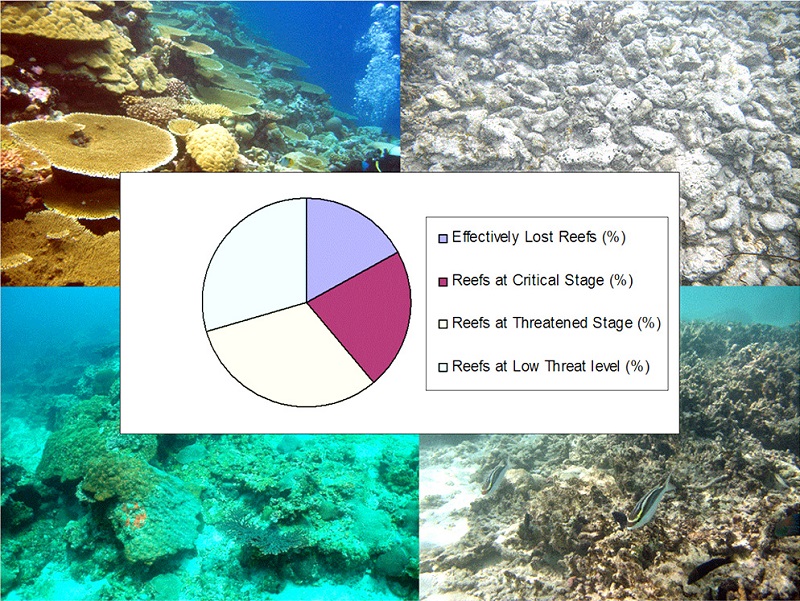

Now consider the regional level. Areas of shallow sea—where biological production is greatest—actually increase in value (in monetary terms at least) when turned into land, when landfill has made it real estate. Of our tropical shallow marine habitats, we are losing 1 to 2 per cent per year and to date we have lost about half of all the main habitats (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Proportions of reef in different states of health or damage, from very good, to completely destroyed. Photographs: examples of the four categories that the pie chart refers to.

The simplest of maths should give cause for massive action, one would think, but it has not done so. Given the above examples and countless others, the reasons why the decline continues become more readily understandable.

A ‘two worlds’ model

The tropical marine world is, in one sense, two (at least) quite different worlds, which intersect on occasion but which at the present time scarcely seem to interact. One world is that of decision makers and of so-called ‘managers’, while the other is that of the poorest sector of society, where the majority of people make a living from their immediate environment. The lack of interaction can be illustrated by some simple, real examples. A golf course was built on fish spawning grounds; I have seen (but the golfers did not) the ruined fishing villages that had to be abandoned when the fish supply subsequently failed. It is not only golf, of course – any number of coastal developments can have similar effects. Shrimp ponds are carved out of mangrove forests but may last only a few years before having to be abandoned for numerous reasons such as toxin or disease build-up. Some areas of Asia are scarred by thousands of hectares of lunar-like craters that are as sterile as the moon, where the felled mangrove stands once provided rich benefits. The idea of making protein is good of course, but shrimp is called the dollar crop because it is exported; the local people cannot afford it. The two worlds may intersect initially by providing labour for construction, but then they drift apart, one to urban flight because their land no longer supports them while the other world seems to float above those problems.

This sounds gloomy, and it is. Many initiatives bring rays of hope – projects that are locally beneficial to the poorest world, but yet the poorest still starve. You usually will not see them of course, but their famine continues.

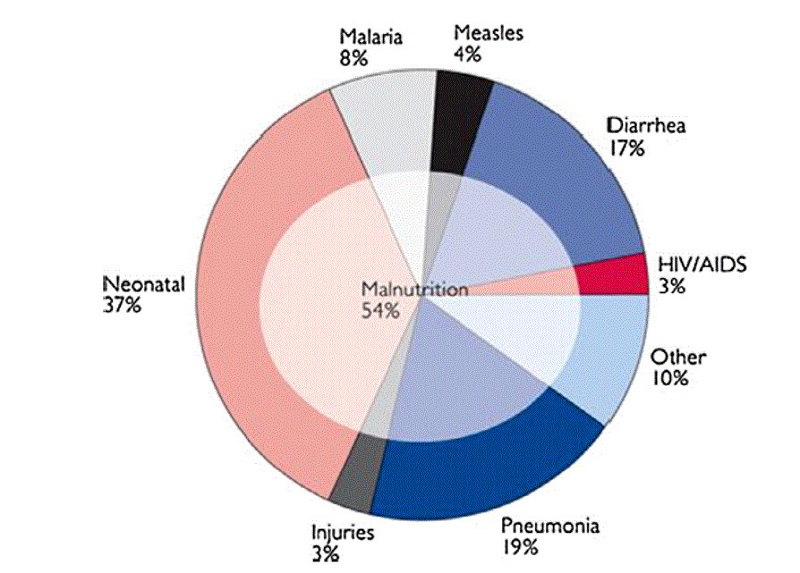

Famine, why use that word? A look at Wikipedia lists many famines, all defined by a region and by dates when they started and ended, with the numbers of people who died. Today, the starvation going on in several tropical countries has no start or end dates, yet the number of people affected now far exceeds those in most of history’s defined famines. Just one example: reports published show that over half of the mortality in under-fives in the poorest countries is due to malnutrition that makes fatal many of those diseases that you and I have likely suffered but fought off with little problem (Fig. 2). Given the high birth rates in such countries, the term ‘over half’ means an awful number of children.

Figure 2. Major causes of diseases in under-fives, showing the contribution of malnutrition (from Bryce et al., 2005).

Remedies may exist, or could be made available, but dependency on protein from the shallow sea remains the main issue. This dependency is almost total for a huge number of people, with many more being partially dependent. Approximately three billion people live within 100 miles (160 km) of the sea, a number that could double in a decade as a result of human migration towards coastal zones.

Management, politics and economic drivers

The present systems and methods of marine habitat and fisheries ‘management’ are clearly failing in a global sense, and this is not sufficiently questioned.

We do not necessarily need more research. We generally already know enough underlying science to avert marine degradation with all its concomitant losses of ability to provide protein, support diversity, support shoreline stability and support people. The issue is more determined now by politics and economic drivers. Some say we can ‘manage’ the marine environment, but this is simply hubris, or conceit. We rarely successfully manage any one species let alone the ‘sea’ or its major systems. The best we can manage might be human impacts on the sea’s potentially rich coastal habitats. Although that does not sound very appealing (stopping things is rarely popular) it is time to recognize that in many cases it is the only sort of management that has a chance of working.

Human laws vs natural laws

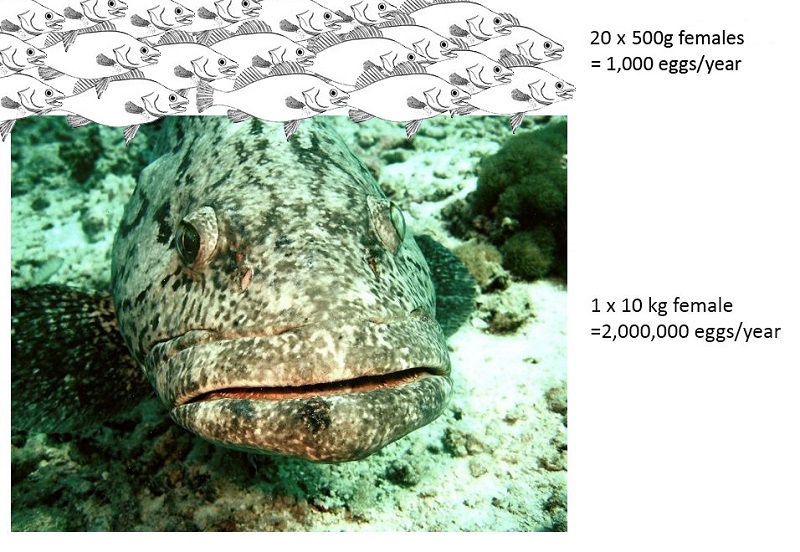

We must also align human laws with what we might call ‘natural laws’. One example from fishing (where data show that ‘management’ has been particularly poor): where regulations do exist they permit capture of large individuals and prohibit capture of undersized ones (Fig. 3). But such regulations can severely exacerbate the problem because it is the older fish of many species that produce exponentially more eggs. If you want to keep up the supply of juveniles then, you need to retain sufficient ‘big fat mamas’. Retention of those will allow people to live off the yield (the interest) tomorrow, instead of today’s widespread practice of using up the breeding stock (the capital). Again, economics is the problem: it commonly suggests that the best way to profit is to catch them all now (someone else will if you do not), sell them, and invest the money into something else when it becomes necessary. This was concluded 50 years ago for whaling and we can see the same happening today with, for example, tuna fishing.

Figure 3. Fisheries rules (where they exist) advocate keeping large fertile specimens and letting go the small ones. Which is best for maintaining a healthy population for tomorrow?

Giant marine reserves

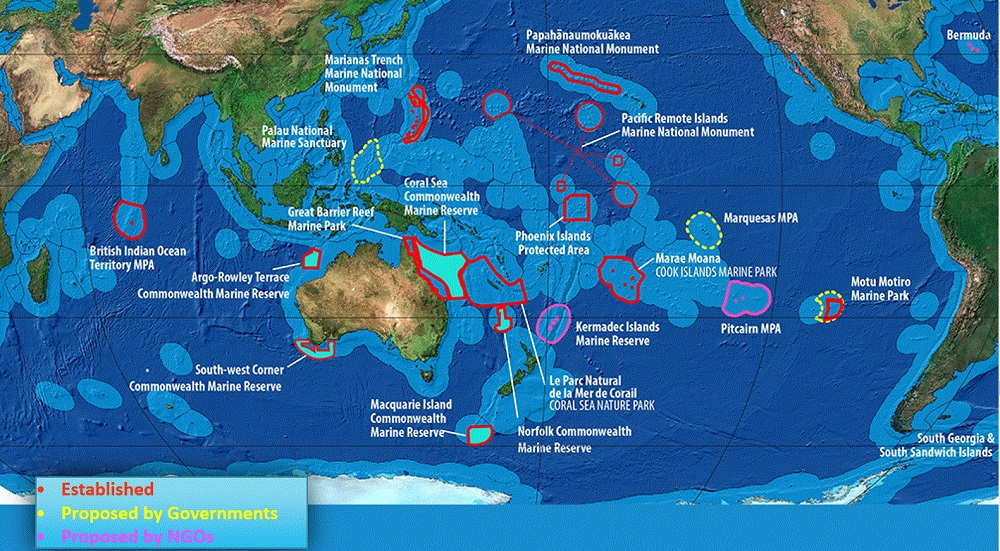

But how do we let the big ones go to breed again next year? There is only one way that I know of, and that is by strictly protecting large enough areas to make a difference. There is now a momentum for creating giant, strictly protected marine reserves and their number is increasing (Fig. 4), although not without predictable and vigorous opposition from fisheries interests. Criteria for creation of large marine reserves must include: they are still rich enough to be worth protecting in the first place; they are large enough to make a regional or global difference; and they must have a governance that can enforce and sustain them. The number of places that fit these three criteria is distressingly few, but they are now an established form of marine conservation. These have made a huge impact on the amount of area protected.

Cynics have asked: “You suggest feeding more people by stopping them from fishing in huge areas?’’ The answer is yes, if done in a carefully planned way. In several Philippines’ examples, strict protection of even modest sized reefs from fishing has resulted after just 3–4 years in several-fold increases in fish yield and incomes. Giant marine reserves scale this effect up.

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) addresses many of the issues and conflicts arising around marine reserves. MSP is in its ascendence, and its need is urgent; you can only keep taking high production year after year if you do not eat into the capital (the big fat mamas). There is no way to do this other than by excluding fishing from significant areas. It takes only a small handful of fishermen, artisanal or otherwise, to deplete large areas of, for example, coral reefs, which is why ‘management’ that tries to integrate extraction with conservation so often has failed in tropical shallow habitats.

Figure 4. Map of the emerging network of very large marine protected areas. Note that for tropical waters where pressures may be greatest, there is only one in the entire Indian Ocean, and none in the Caribbean, mostly due to intense environmental pressures.

Opposition to marine reserves has often been depressing and generally ignorant. In other cases it may be far from ignorant but relies on the audience being ignorant, and those audiences may include the decision makers. Opposition to protected reserves is commonly abusive when the designation of a reserve threatens vested interests. Those supporting conservation efforts may be vilified, in personal terms also, when their science cannot be effectively faulted. Very dubious ‘science’ may be concocted to promote vested interests. (The poor people who depend on the ocean’s produce have little voice in all this and cannot generally speak up for themselves. Quite simply they do not count.) Sometimes the vilification has been amusing, as when one lawyer called me a ‘scientific fascist’ for using data to demonstrate a point. Sometimes the abuse has been libellous too, but, hey, best to let it go – after all, copious informed feedback from colleagues invariably shows that the abuse backfired. The trouble is, the vested interests commonly do not give up – why would they when money is at stake? And law-makers in most places are generally inclined to believe arguments that are most convenient and immediately lucrative (although many educated officials are increasingly enlightened).

Despite all the opposition and the known limitations (‘paper parks’ and so on), marine reserves are here to stay. There is no substitute at present for maintaining diversity and productivity in tropical shallow seas. The way forward now is to improve their effectiveness, not to abolish them as some would have it. Otherwise we will continue to deplete our habitat by 1–2 per cent per year. We must recognize that this rate of decline is simply far too great to control through present ideas such as ‘living in harmony with nature’ or ‘management’ which are commonly promoted by those living in western comfort. We may one day manage to teach ourselves to do that, but as yet we have not – the numbers demonstrate it clearly. Marine reserves must become a key component of the world’s marine systems where they can serve as reservoirs, and sources of food for the future, and reserves of biodiversity. Most may only be buying time, but time is what we need. If (let us hope soon) internationally organized MSP takes off, marine reserves will become a firm component of the global system. Only then might we fairly begin to start using the term ‘marine management’ in a meaningful way.

Charles Sheppard (Charles.Sheppard@warwick.ac.uk) is Professor Emeritus at the School of Life Sciences at the University of Warwick

Further reading:

Fenner, D. (2014). Fishing down the largest coral reef fish species. Marine Pollution Bulletin 84: 9–16

Sale, P. F. et al. (2014). Transforming management of tropical coastal seas to cope with challenges of the 21st century. Marine Pollution Bulletin 85: 8-23

Sheppard, C. R. C. ( 2014). Famines, food insecurity and coral reef ‘Ponzi’ fisheries. Marine Pollution Bulletin 84: 1–4