What happens to Antarctic krill in winter?

Figure 1. Antarctic krill Euphausia superba are a keystone species of the Antarctic ecosystem and are the food of many globally important predators including whales, penguins and seabirds. Examples of krill caught by the plankton net to verify acoustics. © Martin Collins.

Located in the Southern Ocean’s Atlantic sector, the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia is part of the Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (SGSSI) and is surrounded by a marine protected area (see Fig. 2). It has a rich history, steeped in exploration and exploitation, and is known as much for its whaling past as it is for the legendary traverse of Sir Ernest Shackleton, Tom Crean, and Frank Worsley after their vessel, the Endurance, became trapped in the Weddell Sea pack ice in 1915. It is also renowned for the extraordinary wildlife of its shores and surrounding seas, which host some of the most iconic Southern Ocean animals, including numerous species of penguin, seals, seabirds, and whales (Figs 3, 4, and 6). This abundant fauna is supported by the highly productive South Georgia waters, with seasonal phytoplankton blooms fuelled by nutrients carried in by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), in turn sustaining the zooplankton, fish, and a keystone species—Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba), see Fig. 1—on which many depend.

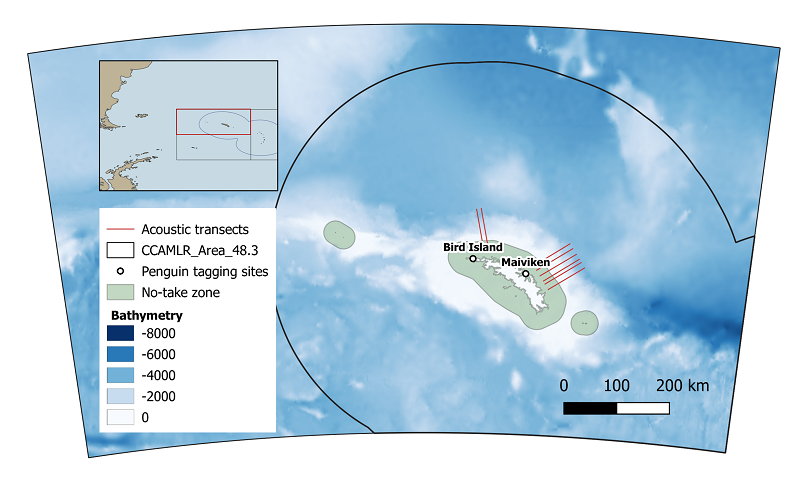

Figure 2. Location map of South Georgia.

Antarctic krill are thought not to be self-sustaining at South Georgia, as sea ice is critical for larval development. Instead, they are transported north-east from the Antarctic Peninsula by the ACC, to become a key prey for many of South Georgia’s marine predators. Due to their abundance, and tendency to aggregate together in vast swarms that can reach up to 100 km2 in area, South Georgia is also a favoured location for a carefully managed krill fishery. To balance the interests of the fishery with the demands of predators, the fishery is managed both by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) who set Southern Ocean-scale catch limits, and by the South Georgia Government, who impose further restrictions specific to the South Georgia region (CCAMLR subarea 48.3). Together, they regulate the operation of the commercial fishery: for example, imposing a maximum annual catch limit of 279,000 tonnes; only allowing the fishery to operate during winter months (outside of key predators’ breeding seasons); and prohibiting fishing inside a 30 km no take zone surrounding the islands. To monitor the fishery’s impact on wildlife, and inform conservation policies at South Georgia, scientists at King Edward Point Research Station and Bird Island regularly collect plankton samples, analyse the dietary composition of Antarctic fur seals, and measure the breeding success of key predators. In addition, krill biomass has been routinely monitored for the last 20 years with the British Antarctic Survey’s (BAS) Western Core Box (WCB) survey work.

Figure 3. Krill are important in the diets of many iconic Southern Ocean seabirds, including the wandering albatross (top), the grey-headed albatross (middle) and the snow petrel (bottom). © Ryan Irvine.

To date, most of the information we have on krill and the ecology and behaviour of key krill-dependent predators is collected in the austral summer, for example through BAS’s WCB long-term monitoring programme, which carries out annual acoustic surveys along pre-defined transects to monitor krill abundance, and spatial and temporal variability (Fig. 2). However, as the fishery around South Georgia operates exclusively during winter, this creates a temporal mismatch between management and the data needed to inform it. Furthermore, whilst a 279,000 tonne catch limit for Subarea 48.3 covers a large area, the fishery tends to concentrate in an area of shelf north-east of South Georgia, coinciding with important foraging grounds of Antarctic fur seals and gentoo penguins, which do not fully disperse during the winter. Recent work suggests these predators may extend their foraging ranges beyond the no take zone, potentially leading to direct competition with the fishery, and this may be exacerbated further in poor krill years. Another concern is that we are now seeing the return of baleen whales, who also rely on krill for their food, yet there is still a gap in knowing how many remain over the winter. Added to this is the fact that fishery catches have been increasing over the last two decades, potentially intensifying the effect of other pressures on krill populations, such as their southward contraction due to regional warming. A clearer understanding of the abundance and distribution of krill during this period is therefore critical.

Figure 4. Blue whales rely on krill for their food and their populations are now increasing around South Georgia after being targeted by commercial whaling in the 1900s. © Amy Kennedy.

This is the background to a 3-year project that started in December 2021, led by BAS in partnership with the GSGSSI and Antarctic Research Trust, funded by Defra’s Darwin Plus scheme. The project centres on surveys of krill and their predators in two consecutive austral winters (2022 and 2023), to gather information on the distribution and overlap between krill, the fishery, and krill-dependent predators.

In each year, we are running at least three surveys that are timed to correspond with the start (May), middle (July) and end (September) of the krill-fishing season. Acoustic transects are essential to obtain the data we require on krill distribution and abundance, and to build the capacity for this, the GSGSSI vessel, MV Pharos SG (Fig 5), was fitted with a scientific echosounder. This will also enable the GSGSSI to continue monitoring the krill after the project ends. So far, we have completed the first full year of surveys and are halfway through our second year. In each survey, six transects on the Eastern Core Box (ECB) were covered, both day and night, extending within and outside the NTZ and focussing on the area with greatest fishery effort. We also obtained comparative data from two transects on the routinely monitored WCB. As the WCB is usually surveyed during the austral summer, this will enable comparisons in both space and time. To determine krill biomass from the acoustic data, plankton trawls were conducted on each acoustic transect, providing the krill length-frequency data which is used in the conversion of acoustic backscatter strength to biomass.

Figure 5. Surveys were carried out aboard the MV Pharos SG which was specially equipped with a hull-mounted echosounder to obtain acoustic data on krill. © Martin Collins.

We also need to be able to understand how krill-dependent predators interact with their prey during winter, and to determine potential overlap between predators and the krill fishery. For this, cetacean and seabird observations were carried out alongside the daytime acoustic transects, so that their abundance and distribution can be estimated. A specialist seabird observer counted birds using standard JNCC (Joint Nature Conservation Committee) Seabirds at Sea methodology during each survey. In July 2022—the time of year we currently know least about—a team of three specialist cetacean researchers joined the vessel to collect more detailed sightings data for whales. Where possible, cetacean photo identification was gathered to provide information on residency, movement patterns and population identity, and photographs of humpback whales are being uploaded to happywhale.com/home for comparison to other Southern Hemisphere images. To gather wider data on the distribution of cetaceans outside of the immediate transects, 12 passive acoustic sonobuoys[1] were also deployed to acoustically locate whales in real time, and record their vocalizations, using funding provided by Friends of South Georgia Island and South Georgia Heritage Trust.

Finally, working with the Antarctic Research Trust, who are providing the project with 12 Wildlife Computers satellite tags each year, we deployed six satellite tracking tags on gentoo penguins at both Bird Island and Maiviken, South Georgia; four in advance of the May survey, and two in July. These send locations by satellite for as long as the batteries last, and do not require the birds to be recaptured to obtain data. We also deployed GPS tags on seven further birds at Bird Island. These provide more detailed locations but require the birds to return within 1 km of a base station to relay the data. Combined, these are providing us with some fascinating insights into the foraging behaviour of the gentoos throughout winter and beyond.

Figure 6. Gentoo and king penguins at South Georgia.Gentoo penguins forage for krill in the waters off South Georgia and variability in krill can affect their breeding success. © Martin Collins.

Work is now underway to analyse and interpret this rich suite of results, which are already giving us unprecedented insights into the ecology of krill during winter. We look forward to completing our second season of surveys and using our results to inform future management of the fishery.

- Cecilia Liszka (ceclis56@bas.ac.uk)

- Martin Collins (macol@bas.ac.uk)

British Antarctic Survey, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET

Follow the project’s progress on our website: www.bas.ac.uk/project/winter-krill-at-south-georgia/

To get in touch or to join our stakeholder mailing list, please email ceclis56@bas.ac.uk or macol@bas.ac.uk

Further reading:

Tarling, G.A. and Fielding, S. 2016. Swarming and behaviour in Antarctic krill. In: Biology and Ecology of Antarctic krill, pp. 279-319. Springer.

British Antarctic Survey. Polar Ocean Ecosystem TimeSeries - Western Core Box. [cited 2023 18/01/2023]. Available from: www.bas.ac.uk/project/poets-wcb/

Ratcliffe, N. et al. 2021. Changes in prey fields increase the potential for spatial overlap between gentoo penguins and a krill fishery within a marine protected area. Diversity and Distributions, 27(3): 552-563.

Baines, M. et al. 2021. Population abundance of recovering humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae and other baleen whales in the Scotia Arc, South Atlantic. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 676: 77-94.

Atkinson, A., et al. 2019. Krill (Euphausia superba) distribution contracts southward during rapid regional warming. Nature Climate Change,. 9(2): 142-147.